As the owner of Engine Room Audio, Mark B. Christensen is renowned as one of the top mastering engineers in music today. Based in 42 Broadway, Engine Room Audio offers more than just audio mastering, including recording sessions and album duplication. And the office space itself has hosted plenty of other entertainment-related companies over the years like Pledge Music, Dubway Studios, Tijuana Gift Shop and Engine Room Recordings.

Although Mark is primarily known as a Mastering Engineer – more below on what that means, in case you were afraid to ask – he led a full life before moving into 42 Broadway. As a musician, Mark was signed to V2 Records and his old band was on the road alongside Radiohead, The Wallflowers and The Gin Blossoms. He had also owned a restaurant downtown. Concurrently, he had worked steadily as an engineer, producer, and session musician.

In talking to Mark – whose credits include work by Trey Songz, 50 Cent, OK Go and The Killers, – I was able to learn more about both him and his field. As he explained, he is a “man behind the curtain,” a person that oversees quality control without most people realizing that such improvements even need to be made. Credit for great-sounding recordings often goes to the main producer and/or lead studio engineer, yet oftentimes the audio mastering helped make the sound mix memorable. For more information on Mark and Engine Room Audio, click on over to www.engineroomaudio.com.

I believe you started off as a musician and turned into a producer and mastering engineer with experience as a restaurant owner and a real estate manager in the midst of all that. When someone asks you what you do for a living, how do you usually respond?

Mark B. Christensen: Yeah, that’s a pretty good assessment of the career path! I usually tell people I’m a mastering engineer, because that’s what I am. I definitely have been producing again more than I did in the previous few years, so sometimes if people don’t understand what a mastering engineer is my fall back is “record producer” or “studio owner.” I sometimes mention the real estate thing, but that was always meant to be second business that me and another “arts-based” guy started about 15 years ago.

What inspired you to make a career out of running several businesses, rather than just being a musician or engineer?

M: Well, I’ve tried to quit this record-making addiction about five times! I’ve been doing it since I was about 12 years old, playing in bands and recording bands. I’ve always loved it and really felt compelled to do it, but at the same time I’ve always rebelled against it because it’s always felt like such a hard life in a way. Really difficult to make an actual living. My parents are both really musical and highly-educated in music. When my parents starting seeing how deep the hook was set, they tried to dissuade me by telling me I wasn’t allowed to do a music degree in college and stuff like that. I guess for me the other businesses were almost a counterbalance to the obsession with music. Kind of like “I’ll go ahead and eat these doughnuts because I’m going to run two extra miles later” or something like that…

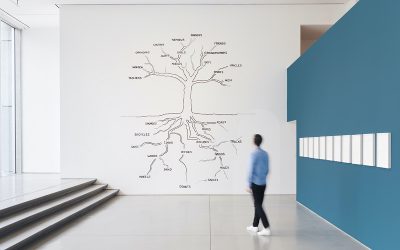

Your studio, Engine Room Audio, is based downtown. What is it that brought you to that area?

M: When we needed to move from our old location, I looked all over the city for a good place to put recording and mastering studios in. Finding the right kind of space, in a building where the landlord understands what you are doing, is pretty hard. I wanted high ceilings, and in New York that can be a challenge too. When we discovered this space, I thought being downtown might be a little weird, but right around the same time we moved to this neighborhood BMI, Red Light Management and later the new label 300 [Entertainment] moved to this area as well, so it seemed like a good place to give it a try. Plus there is tons of mass transit near here. The labels — such as they are — still seem to attach a stigma to being in the outer boroughs, so we wanted to stay in Manhattan.

These days, what does a day at the studio look like for you? How much time is spent mastering versus running a business?

M: I always try and start working on musical stuff around 1 p.m. I get to the studio about 9 a.m. and try to be ready to work on music after lunch, and then I work until about 8 p.m. Still doing 11-hour days after all these years, but my wife forced me to take weekends off once we had a kid, and I’m glad she did…

What is the best way for someone to learn the art of mastering? Did anyone mentor you?

M: It’s an odd discipline. I have assistants who graduated from pretty good audio engineering programs and often they don’t even have a clue what it is, even though they were taught it in school to some extent. I first starting mastering at a cassette duplication company that my cousin and I started back in the mid ’90s. Back in those days, getting a good sounding promotional cassette was almost impossible as most of them were “high speed” copies, duplicated in non-real time. The cassettes that my cousin and I were making were real time, and they sounded great. He is a physicist and I’m an Audio Engineer, so we figured out how to make really good dupes. I knew some people at some of the labels, and they started using our service because our cassettes sounded so much better.

Through all of this, people started to ask me to make their original recordings “better-sounding,” and I did some research into what mastering was, and how to do it. I had a pretty good home studio at that point, so I started mastering for some of our East Village band clients on my home rig. Luckily for me, one of my good friends was one of the head engineers up at The Hit Factory, so I was able to go listen to my mastering work up in those studios, and ask people around there what they thought of it. I was also fortunate that my own band was being produced during this time frame by a guy named Niko Bolas, who, in my opinion, is one of the best producers/engineers ever – also with a crazy discography. He also was giving me feedback and letting me master some of his lower budget projects.

I never interned for anyone, or really had a full-time mentor, but I had an environment where several people would give me suggestions and pointers. It was a kind of on-the-job training in a way. The “professionalization” of the music industry hadn’t really happened so much at that point. You couldn’t really get much audio education from established educational institutions at that point in time. I’m of that last group of self-taught people in the engineering field. None of the engineers who are older than me had any formal training whatsoever. A lot of the guys who are even slightly older than me built their own gear, as it just didn’t exist in a commercially-available product at that point. Things are obviously very different now…

Do you have a production or mastering credit that you’re most proud of?

M: Well, the stuff I’m doing with an artist named Mr Probz has been really fun. It’s super-successful all over the world, multi-platinum in like 15 countries, and he is a great guy and has a great voice. There is a record that I did for an artist named April Smith that I always think of as my best achievement as a mastering engineer, sonically-speaking. The record didn’t do all that well commercially, and in order to fully know what I did, you’d have to be able to hear a “before and after,” which obviously no one but me and the artist’s camp will ever be able to do. They gave me a lot of leeway, and the record was well-recorded by the producer Dan Romer, and I just love the way the record came out. They really let me do my job on that one, which is sometimes not the case, and the final record sounds great. That can be the crux of the mastering engineer. We are kind of the “man behind the curtain” and not many people know what we really do.

What was your first credit that you were really proud of?

M: That’s a hard one because I’ve mastered literally thousands of hours of music, starting with three-song demos and eventually CD’s, etc. I tend to be proud of stuff that I think sounds good, and because I’m a Mastering Engineer, people don’t really hear what comes into my studio, just what comes out. The first thing I remember thinking “oh my god, this sounds amazing” was a live recording I mastered for one of the Bang On A Can composers. It was some kind of an opera about a housewife in suburbia, and the things she had to do. An opera about being a “soccer mom.” I don’t think they ever even released it, but what I was able to do with that recording was kind of a revelation to me. After being able to hear the “before and after” myself, I was convinced that mastering is what I wanted to do…

A lot of people carry the belief that it’s hard to make a living within music, but you’ve been able to do that for over two decades. To what do you credit that accomplishment?

M: Well, it is incredibly hard, no question. And to be honest, I’m not sure I would have made it this far if not for the other business that you mentioned earlier. I don’t want to drive the addiction analogy into the ground, but at some point I realized that I didn’t have any choice but to be in music, and so I sort of created these hedges, to be able to insure that I could continue doing the music thing. I knew it was probably going to be a bumpy road, and I’d seen friends and colleagues have great success one year and total famine the next year, so I looked for ways to “smooth out the trajectory,” so to speak. You’ve also got to make sure your “significant other” understands what’s up. Everybody’s got to be willing to be strapped in for the rocket ride.

Is there a field or career you haven’t yet worked in but would like to try one day?

M: I sometimes wonder what it would be like to do something else, but I guess the answer is really no. My career has a lot of negatives in some ways, but I can’t imagine doing anything else…

What would it take for you to put out another album with you at the helm as a singer and songwriter?

M: (laughs) Time, just time. I ran into Niko Bolas at a conference a year or so ago, and he was like “man, if you write a bunch of songs, I’ll come produce it for free.” I happened to be standing next to some well-known musicians at the time, and they all were like “and I’ll come play on it, too!” I said to myself, “Holy crap, what more incentive do I need?” And I fully intended to do it, I really did…

When it comes to being productive and focused, are there any apps or tools that you primarily rely on?

M: Well, it’s about having good people. I couldn’t live without good assistants and good managers here at Engine Room. We do rely on tons of tech, obviously. We use Google Drive and all its various functionality quite a lot for the office stuff. I know it’s probably not politically-correct to say so, but I’m kind of over the “there’s an app for that” mentality. Usually it comes down to having good people around. We’ve all been sucked into this illusion that we can do anything we want, even without having any skills — make a movie, record a record, build a house, write a book — as long as we have the right computer or the right app. It just ain’t true. Great tools are great tools, but it’s the people that matter.

When you’re not busy working, how do you like to spend your time?

M: My wife and I are really into food. She went to culinary school at one point in France, and I used to own a restaurant, so we have that kind of orientation. We throw really good dinner parties. When we go on vacation we always tie in some kind of wine thing. Visiting a vineyard or whatever. We aren’t wine snobs, but it’s a fun way to understand the history and culture of a place, to know about their wines. Plus, you can pull out obscure but great wines at dinner parties…

Do you have a bar or restaurant that you rely on for a perfect night out?

M: Because we like food, we almost never go the the same place twice. We are always wanting to try new stuff. When we lived in the East Village we used to go to a restaurant called Supper all the time. Great pasta.

Finally, Mark, any last words for the kids?

M: The music industry will live to fight again! It’s a bad time now. A crisis, really. But as they say, there are more people listening to more music now than ever before in the history of the world. Eventually the financial side will sort itself out, and it will be a viable career field again at some point. Hopefully not just wishful thinking…

-by Darren Paltrowitz